Pentridge Prison’s Panopticon

Recent archaeological digs at Pentridge Prison in Melbourne have uncovered three airing yards built in the design of a panopticon. Based on original concepts by Jeremy Bentham, the airing yard design allowed a single guard in the middle tower to keep an eye on each prisoner while they had fresh air for one hour a day.

On the top of a hill in Coburg, near Melbourne, there is a large bluestone building which, at a glance, looks like it could be a medieval castle. The outer walls reach high into the sky and there are turrets on the corners. Yet these walls are not trying to keep the enemy out, but the prisoners in.

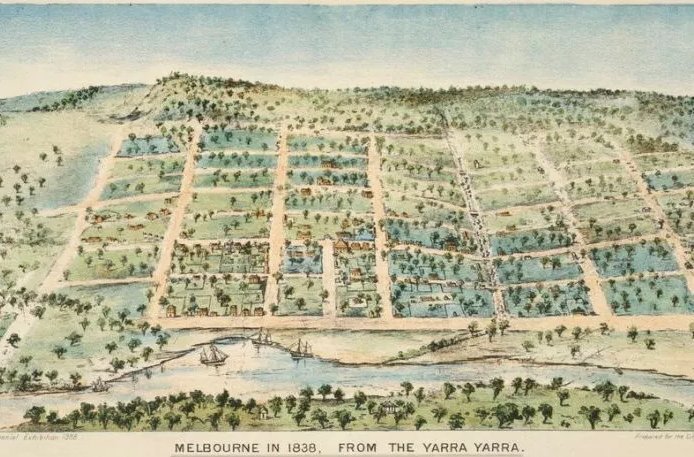

This is Pentridge Prison, nicknamed ‘the bluestone college’. It was built in 1858 when the city was still young. Melbourne had seen rapid growth as people surged landwards towards the goldfields, and experienced all the social problems that go along with it. Old Melbourne Gaol and the prison hulks anchored off Williamstown were no longer coping with the prison population, and Pentridge Prison was built a suitable distance away at the time, but visually impressive to act as a deterrent.

The prison blocks of A Division and B Division operated along the guidelines of the separate system – a prisoner was kept in isolation in a small cell for twenty-three hours a day, during which they could contemplate their crimes and read the bible. Besides a weekly shower and shave, the only reprieve from the cell confinement was one hour a day in the airing yards.

![]()

![]()

![]()

There were three airing yards at Pentridge Prison, built in the form of the panopticon designed by English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham. The structure is in the shape of a wagon wheel, with a guard tower in the centre who can monitor eight prisoners, each in their separate segment.

The panopticon was based on the idea that each prisoner was unsure whether they were being watched and would therefore always behave as if they were. Bentham saw potential in the design being used in hospitals, schools, sanatoriums, daycares, and asylums, but he primarily developed it for use in prisons.

At Pentridge Prison, panopticons were effective in enforcing the separate system. A prisoner was covered in a mask and cowl (called a ‘peak’) and led out to the airing yard. Here, they were allowed to walk for an hour, open to the elements, before being led back to the cells. This gave them the benefit of fresh air and exercise, but kept them confined and isolated. Prisoners spent a month for every year of their sentence in this fashion, the idea being to break their spirits quickly.

The airing yards fell out of use over time, primarily due to prison overcrowding. The last time they were in use was the early 1900s. They were eventually demolished as the prison was modernised, and Pentridge Prison was eventually closed in 1997.

Guest:

Adam Ford

Project DirectorPentridge Archaeological Excavation

Twitter: @AdamFord69

Music:

Collioure – Melodium